This post and the next will take a closer look at one of the “West Coast” climate journeys I mapped in the last post—along the Pacific coast of South America. I’m choosing this one because 1) it incorporates the full range of climates/biomes without large intervening bodies of water, 2) it’s one of the world’s most dramatic in terms of its contrasts, and 3) I’ve been able to travel, relatively continuously, a large part of it during a period when this topic was at the front of my mind.

Before I get into this example I’ll mention why I’m not focusing on any North American ones, which #1 (mostly) applies to and which are relatively straightforward to travel. The reason is that despite their accessibility #3 doesn’t apply. I have visited many places along both coasts but generally piecemeal, with the exception of a high school family road trip from L.A. to Vancouver when I wasn’t yet obsessed enough with this subject to coax everyone into a string of representative hikes along the drive. And the 2020 coast-to-coast drive I wrote about last year hardly involved leaving the car let alone visiting any quasi-natural areas (which are few-and-far-between in the middle part of the U.S.).

The progression of climates and biomes along the west coast of South America is the most dramatic in the world thanks especially to the extreme dryness of the Atacama and Peruvian deserts—in the driest part, around Antofagasta in northern Chile, it basically doesn’t rain—and their latitudinal extent. Both of those aspects result from overlapping conditions that would each likely produce a desert on its own.

Pacific South America—climates/biomes (left) and precipitation levels (right). The white arrows represent prevailing wind direction.

First, at those desert latitudes, the Andes form a high and continuous wall and the prevailing winds are from the east, creating an especially strong rain shadow effect. Second, the subtropical high-pressure zone typically centered around 30 degrees has its usual drying effect, except that for complicated reasons again having to do with the Andes it’s more stable and extends farther north than along other west coasts. And finally, and probably most importantly, the cold Humboldt/Peru Current cools and dries the air all the way to Ecuador where the coastline starts to bend eastward away from the current. (Once again I’m drawing on my new favorite book, Trewartha’s The Earth’s Problem Climates, for most of this background.)

The absolute dryness of those deserts of course produces a heightened contrast with the wet climates to the north and south. But the northward extension of the dry zone (mostly due to the cold current) also means that on the northern side that contrast is compressed, so that the coastline between Southern Ecuador and central Colombia features the world’s sharpest rainfall gradient at sea level. You can see that to a degree in the maps above but I think it’s complex and interesting enough to deserve its own post—stay tuned for that.

In this post I’ll focus on the southern part of the pattern, from the Atacama Desert on the Peru-Chile border south to the temperate rainforests of Chiloé Island and the Carretera Austral (Chile’s southernmost coastal “highway”) in northern Patagonia. To go all the way to the southern tip of the continent by road would’ve required driving into Argentina, through higher and drier landscapes, in order to bypass the rugged intervening coastline. (Someday, though, it would still be nice to make a separate visit to that extreme.)

I made the 3700 km./2300 mi. journey (in fall 2019) by a combination of bus, car and ferry, with the exception of one air travel segment. My goal was to experience and photograph enough reasonably intact landscapes, at roughly even intervals along the route, to later be able to create either 1) a photographic transect of the gradient with only slight variation from one image to the next or 2) one of my fractured watercolor representations.

But as I mentioned in my “Long Gradients” series of posts, I’ve since realized that the fractured/abstract style doesn’t lend itself well to this scale and “linearity.” And even though I knew that having limited flexibility on the trip (for a few reasons I didn’t want to do the whole thing by rental car) would mean any attempt at the photographic transect would be superficial, it became even clearer that the concept can’t really work without using an interval less than, say, fifty miles. Particularly in such a topographically complicated region, where it’s hard to eliminate local variations to the large-scale climatic patterns without choosing the route very carefully, fewer images means less flattening out of those variations.

The Chile “transect” and my generalized route (the plane travel segment is dashed), with climates/biomes (left) and rainfall levels (right). The trip extended a bit further south than the last image I ended up choosing, to the southernmost airport along the Carretera Austral.

So, to create the illusion of a smooth gradient I had to cherry-pick the images I included in the sequence. I ended up using only the six photos above, shot at not-so-even intervals—pretty far from the transect idea I originally had in mind. Obviously if I want to give this concept a serious try it’s going to take a lot more time and energy. But this attempt should still give a taste of the amazing variety along this route and what it’s like to try to take it all in.

Candelabra cactus an hour or so east of Arica, in the Quebrada de Cardones.

The trip began in the town of Arica, Chile, from where I took a two-day excursion across the desert and up into the Andes (the overall north-south journey included a bunch of these side trips). In the lowlands the only visible vegetation is these unique and widely-scattered “candelabra” cacti, restricted to a tiny area along the Chile-Peru border.

A river valley cutting through the Atacama.

I stayed in the desert for another week or so, making my way south by bus and taking a few more detours east and west (you’ll hear more about these later as they show up in some worldviews). For more than half the length of the Atacama, at low elevations, the landscape stayed essentially barren except around water sources.

In a zone centered very roughly around 30 degrees, the prevailing winds start to reverse direction so that they’re no longer blocked by the Andes. From there southward they blow over the cold ocean, presumably bringing less rain than they would with a warm current, but the lack of a mountain barrier is one factor determining the southern extent of the Atacama. Around the city of La Serena, cacti start to appear everywhere as the desert technically transitions to semi-desert, though it still looks very desert-like by North American standards.

Semi-desert in Fray Jorge National Park, a few hours south of La Serena.

I’m actually getting out of order—I’d planned my visit to Fray Jorge on a day when the park turned out to be closed, so I ended up driving all the way up there and back from Santiago on the very last day of the trip. (The worldview I’m currently working on is based on Fray Jorge; when I share it you’ll see why that park was a must-do.) But that detour had the advantage of forcing me to travel that segment of the trip by road, since I originally hadn’t been planning on it. I’d decided to fly from La Serena to Santiago after hearing that the drive isn’t particularly interesting; that turned out to be more-or-less true, but as you’ll hear more about in a moment it’s filling in the “missing link” that really matters.

Along the five-hour La Serena-to-Santiago drive (pretending that I’d done it in the right part of the itinerary) the landscape is mostly agricultural, but in the distance you can see more and thicker forest appearing on the mountainsides. In the Santiago/Valparaiso area the best place to see the matorral (subtropical shrubland, or the Chilean version of chaparral) is La Campana National Park, partly because one of its valleys contains the last significant population of the endemic Chilean wine palm, Jubeae chilensis).

La Campana’s latitude is roughly that of L.A. and this part of the park feels a lot like Southern California. Large cacti are still common this far south; and, while they’re usually associated with humid climates, bromeliads seem to fill the North American niche of yuccas and agaves here and even in drier spots to the north.

From Santiago I flew to Temuco, in the northern part of the wet temperate zone, with the closest airport to Villarrica Volcano and other sites in the Lake District. This region is still too far north for rainforest but was shockingly green after I’d spent so much time in the dry half of the country. This seemed to be a good portion of the trip to do by air since nothing between the two cities had jumped out as a must-see, but I immediately regretted that decision after feeling like I’d been dropped onto a different planet. It felt unmooring to a degree that I briefly considered trying to somehow squeeze that 9-hour drive into the last few days of the trip along with the 10-hour drive to and from Fray Jorge. I gave up on that possibility but, learning that there are in fact a few national parks straddling the dry-subtropical/wet-temperate divide within that segment, I decided it would just need to happen on a future trip. (The urge has quieted a bit since then.)

To fill that missing ecological link in the transect I needed to cheat—by using an image from the wetter, south-facing slopes of La Campana, back near Santiago, which I imagine to be reminiscent of the transitional landscape toward Temuco. (It has more of a Northern California look to it.) So much for the goal of even intervals and minimal topographic influence.

The next image comes from the forest around the base of Villarica Volcano—again I don’t think it’s technically rainforest, but it did feel dramatically different from anything earlier in the trip. Now with a much better overview of Chilean vegetation than I had back then, I realize that this landscape might not really belong in the sequence either; it’s at an elevation of over 1000m and so is probably shaped by altitude to some degree. The forest is mostly beech, typical of mid-elevation forests in this part of the country and closer to sea level farther south. Precipitation-wise it’s probably in the right position in the sequence, but if I were to go back I’d try to visit some natural areas closer to sea level.

The final, rainforest portion of the trip branched off in two directions, with a combination of bus and ferry travel—the first to the Pacific coast on Chiloé Island and the second down the Carretera Austral along an inland waterway (entering northern Patagonia). Most of this region receives more than 200mm./80” of rain annually, with over 120” on the west coast of Chiloé and at higher elevations on the mainland. I chose to officially end the transect on Chiloé because it features that extreme at, finally, a sea-level location.

A boggy part of the forest, including (on the right) some of the country’s southernmost bromeliads—here in their more expected forest habitat, creating a tropical look. (Having spent time here and in New Zealand/Tasmania, I think that our Pacific Northwest rainforests missed out.on a lot)

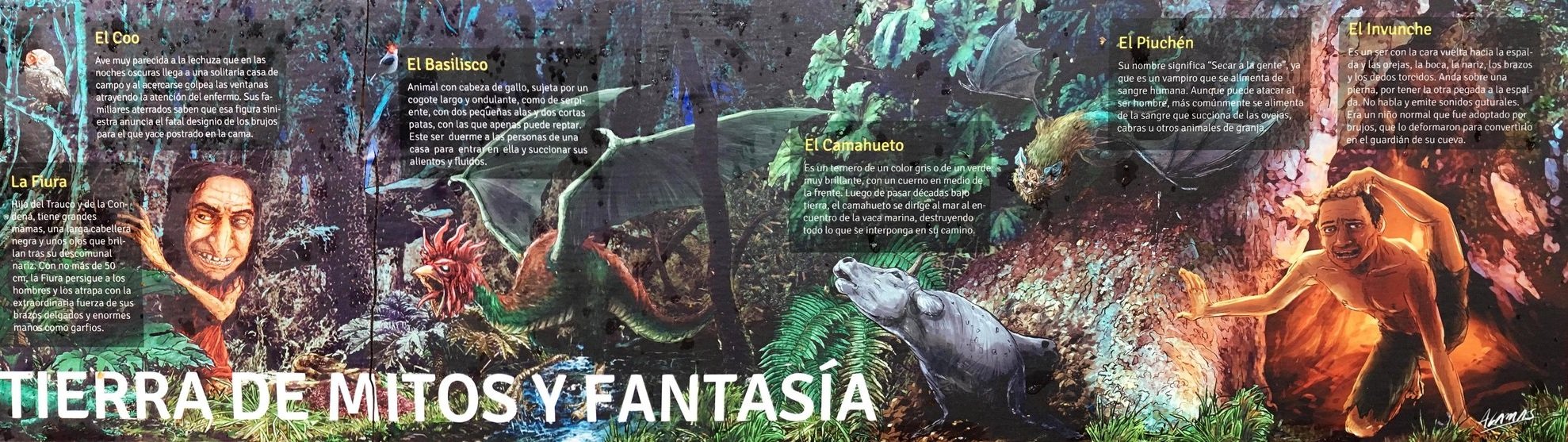

Chiloé’s chilly, water-logged, often stunted forests have an evocatively gloomy aspect that’s inspired some creepy mythology.

Along the Carretera, at least according to the maps, there isn’t such saturated forest near sea level. But since I was able to visit some old-growth there that was no less evocative, I’ll share some of that too.

Pumalin National Park, with giant Alerce cypress (related to redwoods).

Upper elevations of Queulat National Park.

Along the drive.

So if I were to do this trip again, aiming for a lot more volume and nuance with the imagery, I would spend much more time in the transitional zones between the shrubland/mattoral and the rainforest. That would take quite a bit more logistical creativity; having an “in-between” character, these forests are probably considered less evocative than the landscapes to the north and south and so aren’t made as accessible or might be less likely to be protected in the first place. Plus, the mild climates of these zones are particularly amenable to agriculture and urbanization.

Next time, to the north side of the desert….

Darren