My latest “Urban Volcanoes” series of posts looked at islands of nature in cities through a mainly geological/topographical lens (with the exception of Rangitoto Island, which also has ecological significance). The next few will take a more ecological angle on natural relics in urban areas, though topography often has a lot to do with why they’ve been preserved.

In this post I’ll share an article, “The Other Urban Jungle,” that I wrote for the July/September 2018 issue of My Liveable City magazine. It’s an abridged and updated version of a much more in-depth case study I did on Parque Nacional da Tijuca in Rio de Janeiro, both the world’s largest urban park and largest replanted tropical rainforest, for the Large Parks: New Perspectives conference and exhibition at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 2003. You probably already know about this park through images of its most iconic attraction—the Christ the Redeemer (Cristo Redentor) statue.

My study of Tijuca grew out of a primarily design and academic interest in city-nature juxtapositions rather than an artistic one, and I haven’t yet created a worldview based it. But the park is highly relevant to my current pursuits not only because the contrast between dense metropolis and critical conservation area is so stark, in a way that’s significant from both cultural and environmental perspectives, but because its importance is so strongly tied in to the question of what “nature” and “wilderness” actually mean today (see my Realities of Nature posts for a lot more on that topic!).

Below is the full text of the article, along with some of my photography and a few archival images from a thee-week research trip to Rio in 2002.

Darren

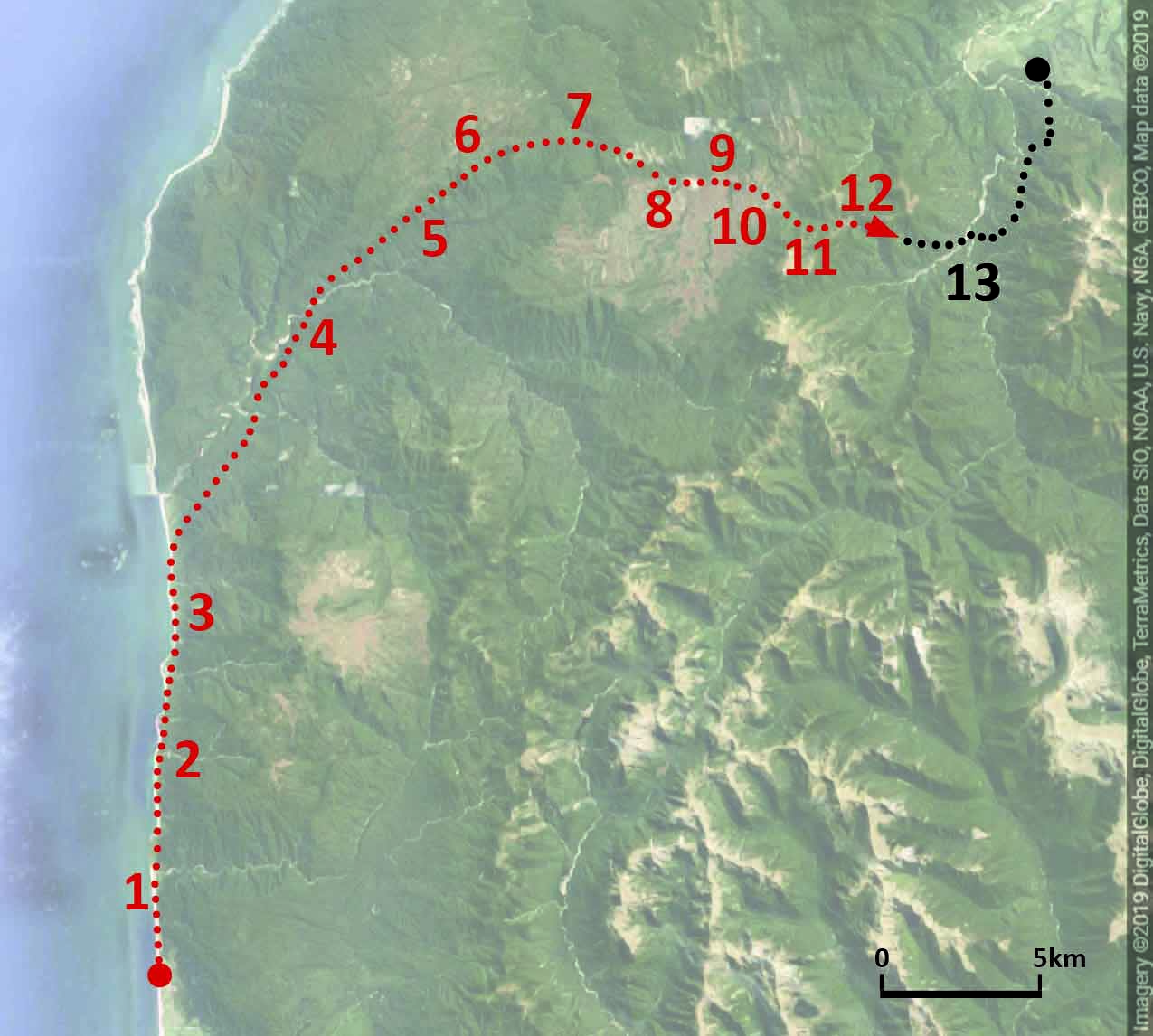

The four sectors of Parque Nacional da Tijuca (my drawing superimposed on Google Earth).

View from near the summit of Pico da Tijuca, the park’s highest point.

Parque Nacional da Tijuca, sprawling over 3,953 mountainous hectares in the heart of Rio de Janeiro, contains arguably the largest urban forest and the largest replanted tropical forest in the world. Formally declared in 1961, the park is a unique and fascinating synthesis of culture and nature. Not only are playgrounds, ornamental sculptures and fountains, and picnic areas backed by rock faces rising five hundred feet above one of the world’s most endangered ecosystems; the forest itself is a human creation that, when set against the teeming metropolis encroaching on its boundaries, could not appear more “natural.” But Tijuca is noteworthy not only as an island of native forest in an increasingly dense and challenging urban setting; the well-being of the city itself has always been intimately associated with the fortunes of the environment that the park now struggles to preserve.

Tijuca rises from 80 to 1,021m in two ranges running parallel to the coast and together referred to as the Tijuca Massif—a dramatic landscape of isolated peaks, deep valleys, and vertical rock faces punctuated by numerous caves and waterfalls. The park’s four sectors of forest are relics of a rainforest that once extended from the Uruguayan border to the northeastern tip of Brazil. Known as the Mata Atlântica, this ecoregion is older and more diverse than its Amazonian counterpart and has been nearly eliminated due to its location in the most densely populated part of the country.

Remnants of infrastructure from Tijuca’s coffee-growing era.

By 1840, most of Tijuca’s original rainforest, with trees reaching heights of 45m and diameters of more than 2m, had been cleared for coffee cultivation. Yet the Massif represented a valuable resource for the city not only because its cooler, wetter climate provided ideal growing conditions: its streams represented Rio’s only source of fresh water. With diminishing forest cover the watercourses began to vanish during the dry season and flood during the wet, and between 1824 and 1844 a series of droughts had made the situation critical enough to endanger the city’s growth. In 1861, a radical governmental decree called for the restoration of the watershed. The slopes were to be reforested with indigenous trees—a degree of farsightedness that is surprising and refreshing to discover existed at that time, given that a monoculture of fast-growing exotics would have provided more immediate results and would have been more efficient to plant. By 1871, 60,000 trees had been planted, with a survival rate of about 80%. In 1877, an unofficial decision was made to transform the Tijuca Forest, the most level and formerly most devastated sector, into a public park—an escape from the heat and congestion below incorporating plazas, roads, trails, bridges, fountains, and ponds in the style of Paris’ Bois du Boulogne. Also included, for the first time, were numerous exotic and ornamental plants in the vicinity of these features.

Cascatinha Taunay, one of the park’s main attractions, now and in the early 1800’s. (Engraving: Johann Moritz Rugendas, Cascatinha da Tijuca, 1822.)

Forest paths (not the same path, but in the same general area)—now, and in the late 1800’s soon after replanting. (Left photograph: Marc Ferrez, Pico do Papagaio, c. 1880?.)

Public amenities are well-integrated into Tijuca’s dramatic landscape.

One of the park’s small ornamental gardens (this one built around part of the original hydrological infrastructure).

View of Cristo Redentor in the distance from another ornamental area of the park.

Since the park’s creation, the forest itself has generally been left in a state of natural regeneration and is today overwhelmingly the dominant experience of the park, with designed spaces and structures covering less than 5% of its area. The replanted zones form a nearly continuous canopy and have regained a diversity and luxuriance that amazes many visitors (and even scientists) familiar with the site’s tumultuous history. Despite compositional and structural differences from the original forest cover, the present-day forest has been found to contain over 1500 species of mostly native plants, about 400 of which are considered rare or endangered. In 1990, the park was recognized by the United Nations as part of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest Biosphere Preserve.

As the city has expanded and densified, civilization is once again exerting serious pressures on the park as an ecological system, including pollution, human-caused forest fires, illegal plant extraction, invasive species, and the overall strain of about 1.5 million annual visitors. Even more dramatic is the proliferation of shantytowns, or favelas, as rural poor and displaced urban residents have migrated to occupy Rio’s last affordable enclaves—erosion-prone ridges and slopes. Today there are close to fifty favelas situated on the perimeter of the Tijuca Massif, home to one-third of the city’s total favelado population. The resulting deforestation threatens not only the forest itself: every rainy season, the Massif unleashes several football stadiums’ full of silt and boulders onto the city below, often with significant losses of life and property.

A favela climbing the slopes of the Tijuca Massif.

The relationship between Tijuca and Rio de Janeiro merits special attention because of more than its complex history. It is likely that the encroachment of the city has, in tandem with the re-establishment of the forest, in fact conferred upon the park an even greater physical and psychological importance to the city’s residents. Today, passing within minutes from Rio’s dense neighborhoods and slums into the Massif’s luxuriantly green (and noticeably cooler) landscape, it is clear that the original importance of the park as a retreat from the city has not diminished. Even from miles away, Tijuca’s lush and evocative terrain seems to breathe life into this metropolis of over twelve million people, boasting more trees per person than any other city despite an overall scarcity of open spaces. The Massif’s ruggedly picturesque profile is visible from nearly every point and often dominates the urban landscape, contributing to Rio’s identity as one of the world’s most beautiful cities. Such natural beauty even compensates in part for the city’s harsh social realities, and raises quality of life to an extent that could attract forms of economic development—namely, clean and technology-oriented industries—with the capacity to improve the very social and environmental conditions that threaten a peaceful coexistence between park and city. Rio thus provides a particularly dramatic example of a city where growth and prosperity can be driven rather than impeded by protection of its ecological assets, protection that is potentially self-reinforcing in that its social and economic benefits may in turn facilitate stewardship of those very assets.

Religious offering, technically prohibited but unofficially tolerated in deference to Tijuca’s multi-faceted cultural significance.

Massages right along the main park road.

Looking up at Pico da Tijuca from the city streets.

Tijuca, today managed jointly by the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (part of the Ministry of Environment) and the municipal government, is perhaps unique among urban parks in that the maintenance of its public image as both a pleasant and “natural” alternative to the city is mainly accomplished through the park’s embracing of the natural reconstitution and maturation of the forest, rather than more typical park maintenance practices. Ornamental garden areas are comparatively tiny, and there is no aesthetic “enhancement” of the forest itself. Despite the 2008 Management Plan’s comprehensive detailing of conservation, research, and educational needs and goals, however, resources are not adequate to support significant efforts to adequately combat ongoing threats to forest health and cover that are once more, within a century, expected to reach levels disastrous for the surrounding city.

Visitors at the Cristo Redentor.

Likely no other urban park in the world has had, over its history, a more diverse set of impacts and meanings than Parque Nacional da Tijuca. But despite past and present challenges, the contemporary visitor’s immediate impression of its landscape is not one of historical upheaval nor of current threats to its integrity. Rather, the unexpectedly lush and mature forest, on weekends teeming with generally respectful visitors truly relishing their surroundings, provides evidence that the perception of “wilderness” can still have a physical and psychological place in contemporary society, even (and especially) within an urban jungle of the more usual kind.