Happy New Year everyone! Despite the covid situation my Italy trip earlier this month (International Cartographic Conference in Florence plus some volcano-focused sightseeing in Naples) ended up going smoothly—more on that in my next Newsletter! For this post I’m going to wrap up the current Australia tour with a work inspired (mostly) by a place that’s a bit more well-known than the others I’ve described—Uluru, formerly known as Ayers Rock. It’s actually one of my earliest “fractured” works in watercolor, completed soon after my 2017 Australia travels. But, I think it’s interesting to re-visit now since it represents a special case of my earlier inclination to mix and match fragments of widely separated places in the same composition, in order to enhance a place that I feel is incomplete on its own.

Uluru at sunset.

Uluru’s located in the Northern Territory, in what’s called the “Red Centre” of Australia for obvious reasons. Contrary to popular conception the region isn’t a desert but more like a mosaic of arid grassland and shrubland; around the perimeter of the rock, where runoff collects, there are patches of forest. The rock itself is a sandstone monolith that, incredibly, is actually turned on its head—it’s several times taller (deeper underground) than it is wide. There are some tiny pockets of vegetation, including a tree or two, around temporary pools on the surface but it’s essentially bare rock.

Close-up of the rock, with forest at the base.

Another, more vertical section of the monolith wall.

Eucalyptus and sandstone.

Most of my visit consisted of a 10km walk around the base (I was pleasantly surprised to find a package tour that included it). Until it became prohibited just a few weeks after I was there, it was also possible to climb the rock, though strongly discouraged. The traditional owners of the land (the Anangu, to whom the site was handed back in 1985) considered it disrespectful to a sacred place; it also polluted runoff that supports wildlife around the base of the rock. Plus it was dangerous—a chain guided climbers up the steepest part, but there were still many accidents as well as plenty of heat- and exertion-related problems. I gladly took these as reasons not to do it, given how much I was trying to cram into that trip; otherwise I definitely would’ve succumbed to a fear-of-missing-out.

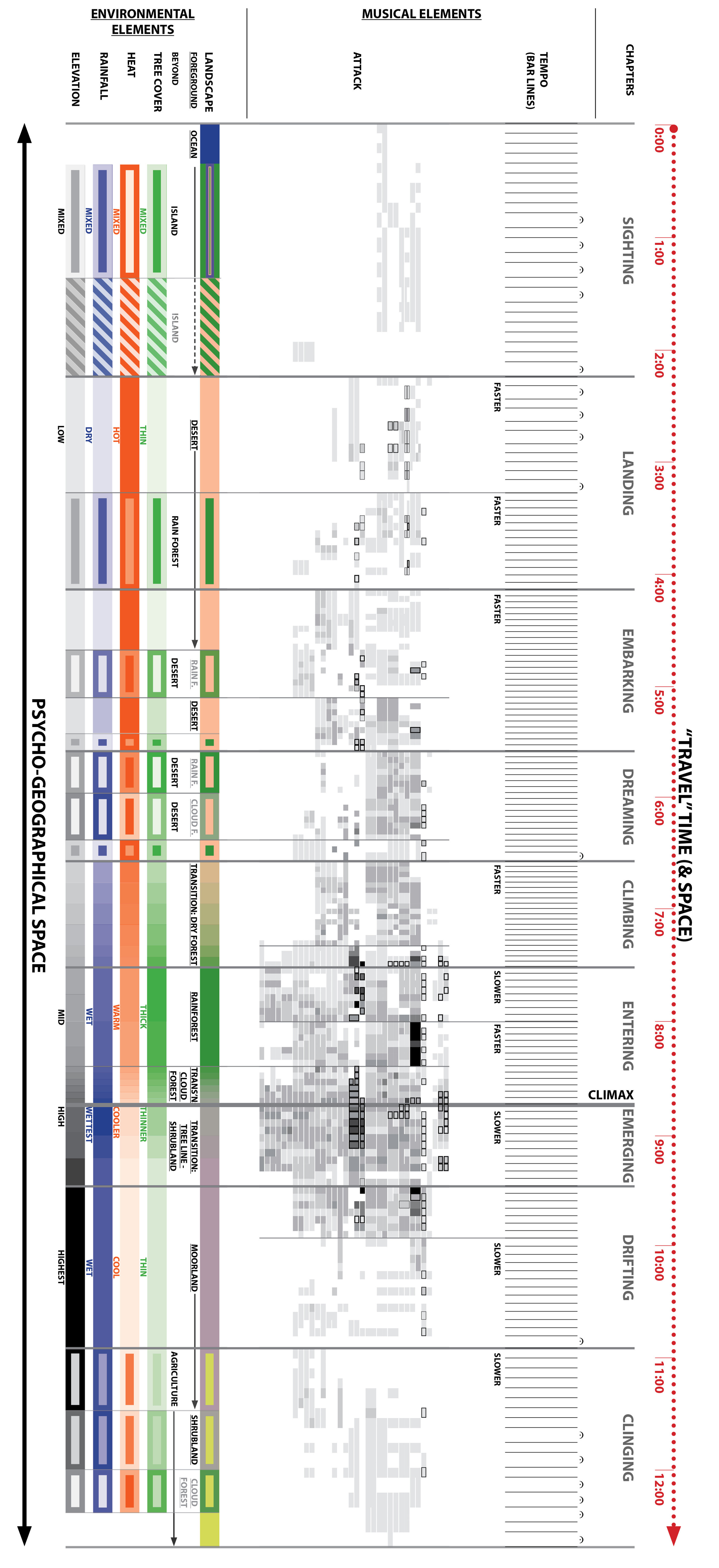

Rock, watercolor on paper, 20”x26,” with fragments depicting views from the 10km base walk and the imagined summit. This is one work where the compositional pattern is inspired by a physical characteristic of the place, in this case the striated patterns in the sandstone.

The highlighted base walk and (lighter) summit trail, somewhat abstracted from the actual routes. The line is broken at the perspective views where I was “standing” off the edge of the paper.

But seeing only the perimeter created a unique challenge for the worldview that would grow out of that day trip. I couldn’t fully “know” the place—i.e. also experience the top of the rock, and the views from it—to the extent that was theoretically possible. Since the goal of the fractured compositions (when they depict a single locale) is to provide that “knowability,” I had to either uncharacteristically leave the summit as figurative black box, inserting the aerial satellite view without anything more immersive, or splice in a different location altogether. Since I was used to cobbling together disparate places in other works, I took the latter approach, using features taken from nearby Kings Canyon. It’s another red-hued landscape, for me most notable for its native cycads. I imagined that the summit of Uluru featured a pool ringed by these cycads, making the entire site essentially an island-within-an-island—an oasis within a giant rock within a plain—in line with my usual islands-and-edges theme. (The oasis was actually a mixing-and-matching job itself, since I had to “transplant” the cycads from their habitat in the canyon to the rock pool which is some distance away.)

Cycads at Kings Canyon.

Pool in another part of Kings Canyon, inspiration for the imagined oasis atop Uluru.

So aside from the usual edge/island aspect, the cycad oasis is meant to represent a sort of special yet forbidden landscape, more dreamlike than physical. Writing this now, I’m realizing the connection of that vision to the actual sacredness of the site, and thinking that filling my experience gap with the oasis was kind of a cop-out. It might’ve been an interesting challenge to be more subtle, taking that idea of dreaminess and applying it to what probably actually exists on top of the rock (albeit in a fuzzy, abstract way) rather than something that definitely does not. Maybe another, future version? In that case I’d make more of an attempt to understand the actual sacred meaning of that site, though I expect that’s something I’ll probably want to leave alone….

Ok, that’s all for Australia, at least for the time being—next destination TBD!

Darren