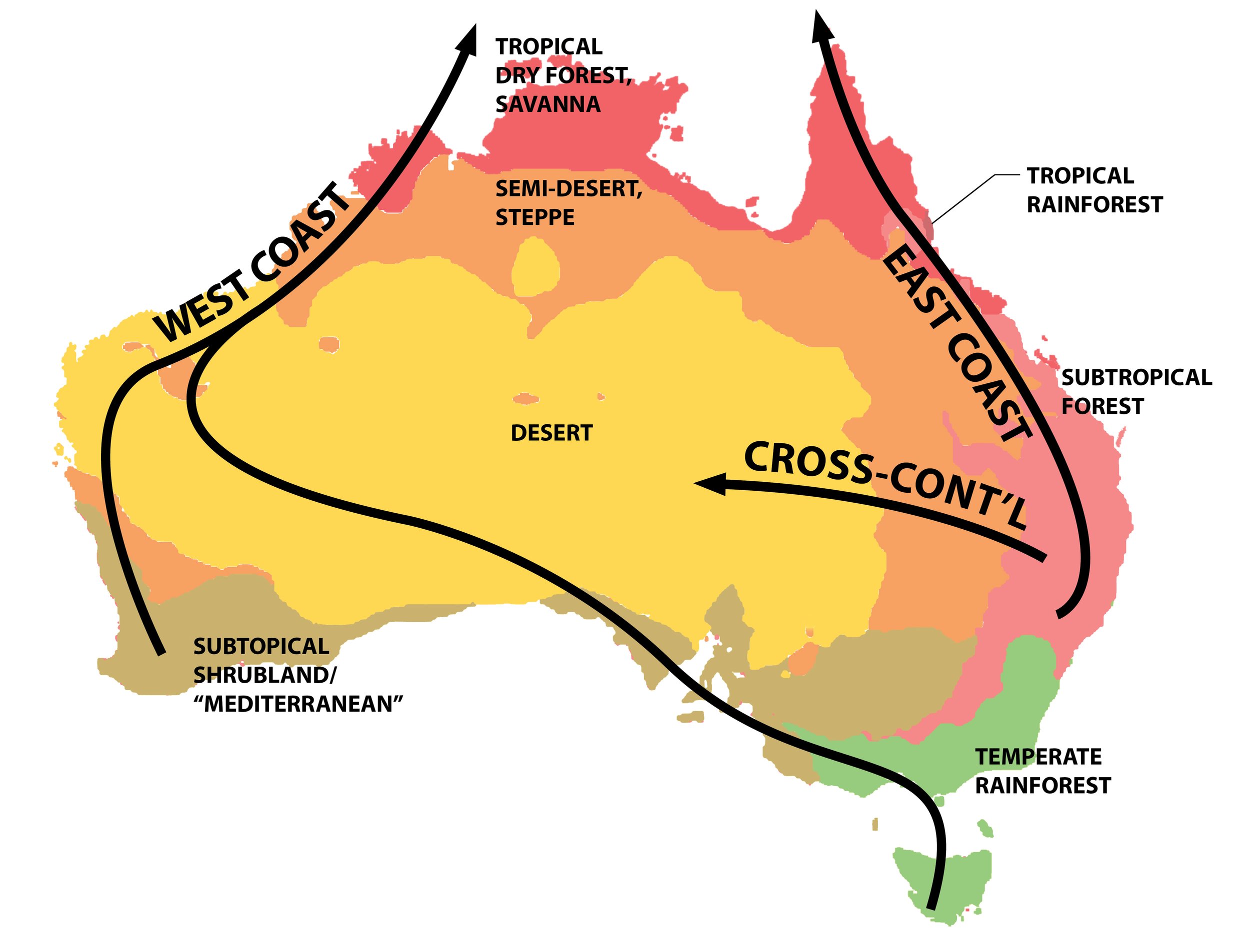

My previous posts in the “Climate Journeys” series have focused on three typical types of climatic pattern—”East Coast, “West Coast,” and “Cross-Continental”—that repeat across different continents. These last few entries will deal with exceptions to those patterns that I find interesting because of their divergence from those typical conditions. Today I’ll focus on eastern Australia, the only place in the world where temperate rainforest transitions to tropical rainforest. (The continent doesn’t extent far enough south to incorporate a subpolar rainforest ecoregion.)

Climatic patterns in Australia, with the temperate continental part of the typical “East Coast” pattern “replaced” by temperate rainforest usually associated with west coasts. Note that Australia’s (lowland) tropical rainforest ecoregion is tiny—found only around the Cairns region (so the coastal patterns couldn’t really be called complete without extending northward into Indonesia/Papua New Guinea).

Temperate rainforest zones, part of the “West Coast” pattern, are typically separated from their tropical counterparts by much drier climates and a few thousand miles or so (i.e. from the Pacific Northwest across the Sonoran desert to Central America, or from Patagonia across the Atacama to Ecuador/Colombia). And along east coasts, where those drier zones are typically absent, temperate rainforest climates are absent too (again this is broad-brush and topography-blind; a few pockets of temperate rainforest do exist in the Appalachians and some montane areas of Japan for example). But in eastern Australia, as I’ve shown before (and you can see more zoomed-in here), the Southern Ocean has the effect of wrapping the maritime-influenced “west coast” pattern around to the southeast corner of the continent, replacing what would be climates similar to the northeastern U.S. (i.e. cold-winter continental) if the landmass extended toward Antarctica.

So the shape of Australia places both temperate and tropical rainforest zones on the east coast, without intervening desert/semi-desert zones. A large region of subtropical forest and tropical dry forest/savanna, though, still sits in-between—not arid, but (analogous to most of Florida for example) not rainforest. This is where a unique aspect of Australian forest ecology comes in: rainforest habitats don’t necessarily align with the rainforest ecoregions. Relicts of a cooler, wetter period, when the continent was situated farther south, are a string of “islands” of rainforest vegetation extending all the way from the temperate to the tropical regions—across zones where localized environmental conditions allow it to thrive where rainfall alone isn’t sufficient. This includes the relatively dry intervening subtropical forest and tropical dry forest regions, but also the southeastern temperate “rainforest” zone where in fact rainfall isn’t uniformly high and isn’t the only factor influencing vegetation. (Again I’ve greatly generalized the ecoregion designations in order to highlight broad global patterns.)

Distribution of “actual” rainforest habitat, grading from temperate through subtropical to tropical. (It’s necessarily simplified at this scale—there are other, much smaller pockets interspersed with these, and the ones shown are certainly further fragmented.)

The environmental conditions determining the distribution of these rainforest islands interact in complex ways, but as described in-depth by D.M.J.S. Bowman in Australian Rainforests: Islands of Green in a Land of Fire, the most important of these conditions seems to be protection from fire—by topography and to some extent the self-perpetuating cool, shady rainforest environment itself. (Unfortunately those protections have proved to be less of a match for the increasingly intense wildfires of the past few years.)

You could argue that these islands don’t actually form a true “rainforest” gradient, since they exist somewhat independently of rainfall levels. But in terms of species composition, ecosystem structure, environmental conditions, and experiential quality they either have a lot in common with the high-rainfall regions at either end of the transition or, in the central portion, make up an intermediate subtropical rainforest zone. In fact in Australia the term rainforest is used to refer to a habitat/ecosystem, not just an ecoregion, and it’s purposefully written as one word in order to deemphasize rain as the determining factor (I typically write it as one word just out of habit).

My personal experience of rainforests along the gradient, on my first Australia trip in 2010, was a bit scattershot, but here are some representative images.

Temperate rainforest in a “fern gully,” Great Otway National Park, Victoria. These lush gullies are particularly good examples of rainforest-supporting microclimates.

Tree ferns in Great Otway, probably the most identifiable plants in the temperate rainforests.

Tropical rainforest near Cairns, Queensland—the diversity in species and life forms is noticeably higher than farther south.

More tropical rainforest near Cairns (Daintree National Park).

A fairly significant percentage of this rainforest archipelago is protected in national parks, but the warming and drying climate will have significant effects—fire-related and more—on the health of individual forest islands as well as on the overall pattern of species distributions and ecological character. Even while it remains intact, though, the temperate-to-tropical transition is challenging to take in over such long distances in the real world, not to mention from a few selected photos like these. It might be another “long gradient” that could lend itself well to my photographic transect idea.

Darren